dedicated to a happier year

November, 2020

Living in a society defined by profit, power, and dehumanisation, it seems as if our feelings were not meant to survive. Much of contemporary art today is made in this vein; preoccupied with aesthetics at the expense of life outside the gallery. Particularly now, where few words, if any, can describe the heft and strangeness of pandemic life, the space to feel — and express our feelings — is even more necessary. In recognition of this, artist Jason Phu has created a project that expresses shades of feeling, documenting the things we feel, but don’t articulate.

In collaboration with photographer Sly Morikawa, best known for her ethereal portraits saturated with glamour and sex, what we used to be, where we used to go Jason Phu’s research into Chinese history, culture and mythology. Across twelve photographs — whittled from five-hundred images — Phu has imagined this folklore through his peculiar, but recognisable punk-graffiti-irreverent aesthetic. In a soft focused haze, Phu dismantles these histories, sifting through what matters most to him and plunging these scenes into the borders of narrative. Phu notes “there are strands of mysteries in the show. It’s a reference to us as creatures, to the big bang, the future, the expansion of the universe and how an artist might interpret that. It’s about all these grand narratives, and the petty, small ones. That’s what I enjoy the most… the big and small in the same place, not where things are big or small, but just exist.”

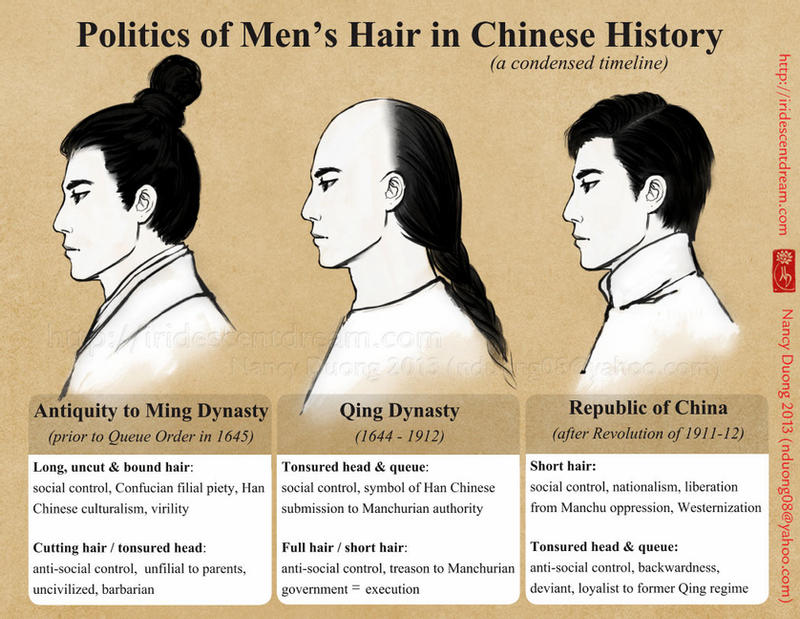

In be as strong as a mountain and as fluid as a river they said. they were wrong, the mountain was a mound of old tv monitors and the river was a dry bed of ox bones (2020), eight colourful figures, dressed in fluorescent cloaks wear roughly hewn cardboard masks decorated with long strands of hair — a reference to Chinese antiquity, where long hair constituted Confucian piety and respect. These sages, shot in a suburban swimming pool, are a manifestation of the Chinese dragon King — the god of weather and water. Unlike the original folklore’s four dragons, Phu has multiplied them into eight dragons — an act of mistranslation that reflects the ever-changing whittling down and workings of oral history traditions like the Chinese diaspora culture of which Phu belongs. He says, “that’s the thing about ancient mythologies. They’re mutable, especially when retold in the new country. There is a shallow shell of authenticity from the mainland that is frozen in time and doesn’t exists anymore.”

In the daytime counterpart of this tale, imagine being the eight dragon kings of all the seas with all the power of the forces of nature and mystical powers of everlasting life and wisdom of the ages and still drowning in your own soup of feelings and left-on-read messages, 2020 depicts the same water dragons with a different and stranger unremarkableness that drains them of any higher spiritual authority. In this contradiction — depicting serious subject matter through the comical pointlessness of the everyday — lies the magic of these works. The jumble of individual jokes, references and poetry of the titles correct, contextualise, and revise each other. If you are deeply attentive to the chaos, your mind will be quieted by the subtlety of the works.

It is jumble of artistic strategies which stirred Morikawa and Phu to collaborate. Phu describes this collaboration ‘a bit more fun, a bit more intuitive’ than his recent history projects, including The Burrangong Affray at 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, where the artist explored Australian Chinese race riots during Australia’s gold rush in 1860 – 1861. While the stakes might seem lower, without having to carry the load of academic research, field work and community stakeholders, what we used to be, where we used to go still carries Phu’s hallmark sense of complication and expansion — blurring conceptions of identity, community relationships and history. Into this mixture of conceptual interests, he drops into the ingredients of deadpan humour, non-sensical narrative, biographical details and poetry in order puzzle, awaken and torment his audiences as they spend time with these compositions.

Through mutual respect, the artists were able to find a familiar dialect, fusing the gap between their different backgrounds — fashion photography and fine art respectively. Phu tells me, “Sly brought a whole new language to the project, how to talk to the models, how to position them. Those instructions are like brushstrokes. It was a nice collaboration; giving up control.” By working together, the pair have created a time capsule of a moment in culture and their own lives. The result is a set of images that explore identity through poetic metaphors, critical intelligence and a humour and irreverence that is never heavy handed or laboured.

Gliding through different registers, mythologies and moods, each scene in what we used to be, where we used to go forms a loose web that adds up to a wider picture. By leaning into the photographic medium, Phu has tapped into a new language to express the ideas of his practice. And in doing so, these works open a new emotional register; straining with unacknowledged feeling and a mystery that speaks to the current moment. It is this sense the knowing and unknowing of these scenes that gives this series their potency. This is classic Jason Phu — something new from something gone.

END.

This text was originally commissioned by Chalk Horse.