jack in a box: notes on kaldor public art projects, michael landy and the archive

February 2021 —

0. connected, communicative and co-dependent

Art is a story with many beginnings and possible endings. Central to mapping these storylines is the archive — a system of storying, logging, pigeonholing, registering and recording. The archive, whether real or virtual, offers recorded material a logical order, framing its meaning while preserving its access for the future. In recent history, cultural institutions have transformed historical conceptions of the archive — once synonymous with boxes of unloved static documents — by imbuing them with life and a sense of happening to reveal the tensions, hidden stories, and interrelationships that are a part of people, projects and processes.

A primary means to animate the archive is the exhibition (although I should note that many archives are comprised of exhibition remnants). A public display of material, the exhibition is one of many, albeit the most popular, vehicles for the learned study, criticism and display of artworks and information. Exhibition making is fundamentally a question of connection, with curators tasked with finding ways to connect art with the world outside of the gallery. Through their own questioning, assessing, judging and interpreting, it is the curator’s role to empower artists with the information, and confidence to communicate their stories — and in the most meaningful exhibitions, stories that aren’t heard, or whom no one thinks they want to hear, or haven’t yet heard.

This writing, Jack in the Box: Notes on Kaldor Public Art Projects, Michael Landy and the Archive exists as part of the Kaldor Public Art Project’s desire to animate their own archives. At the organisation’s invitation, I have woven together a loose catalogue of thoughts that thread together eleven objects selected from the Kaldor Public Art Project Archive. Borne from my self-directed research into the realities and contradictions of this archive, I’ve focused on the agency and materiality of the archives themselves in my research, selecting items that reflect upon Michael Landy’s role in using the archive as a means to create new artistic outcomes, Project 35: Making Art Public (itself a project of animating archives) while also exploring Landy’s relationship to John Kaldor and Kaldor Public Art Projects.

1. touching history

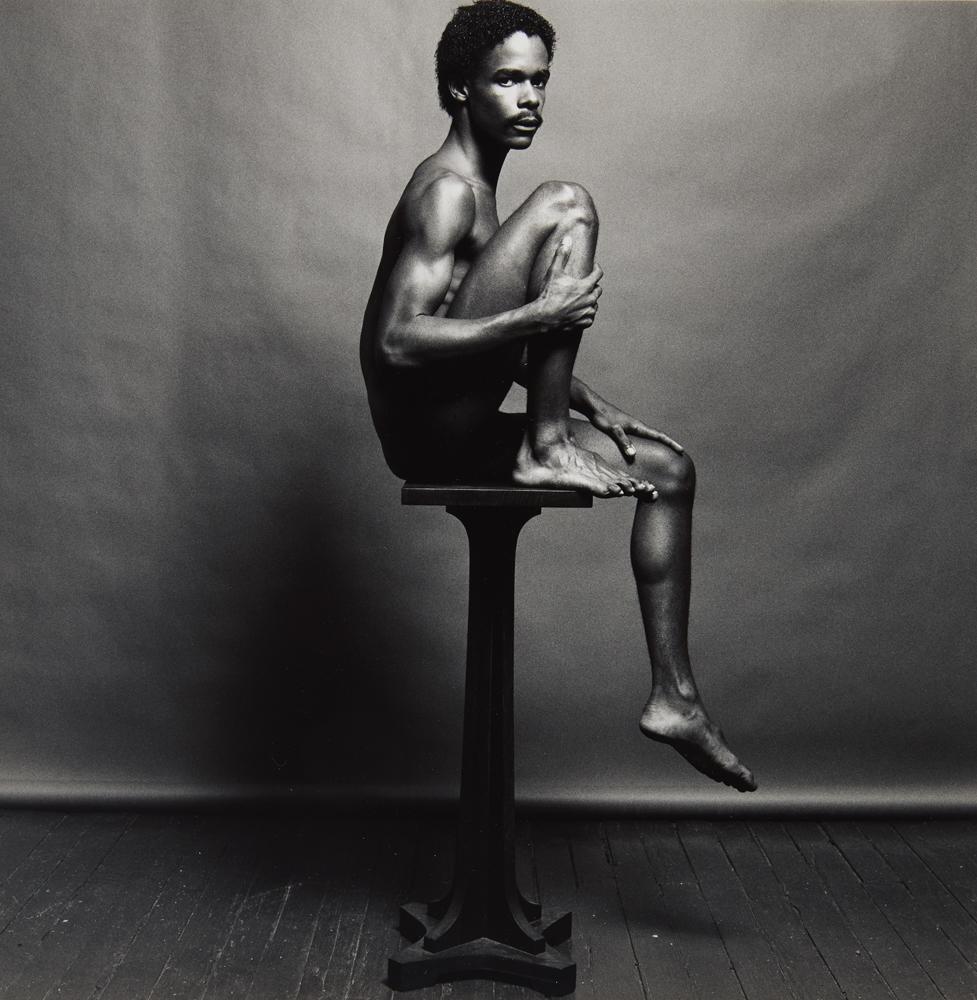

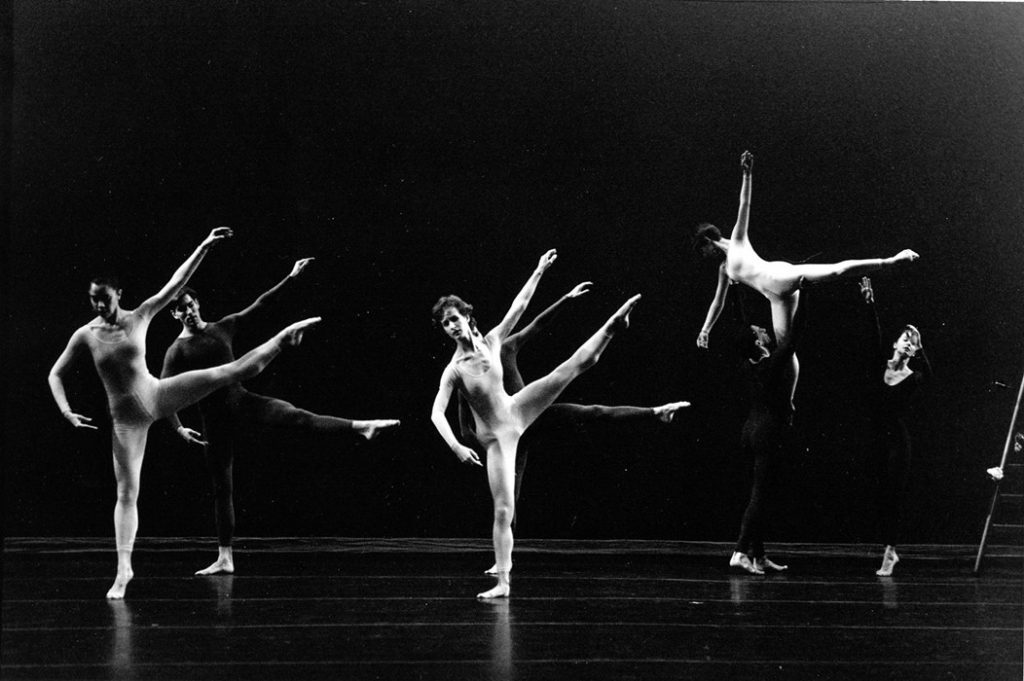

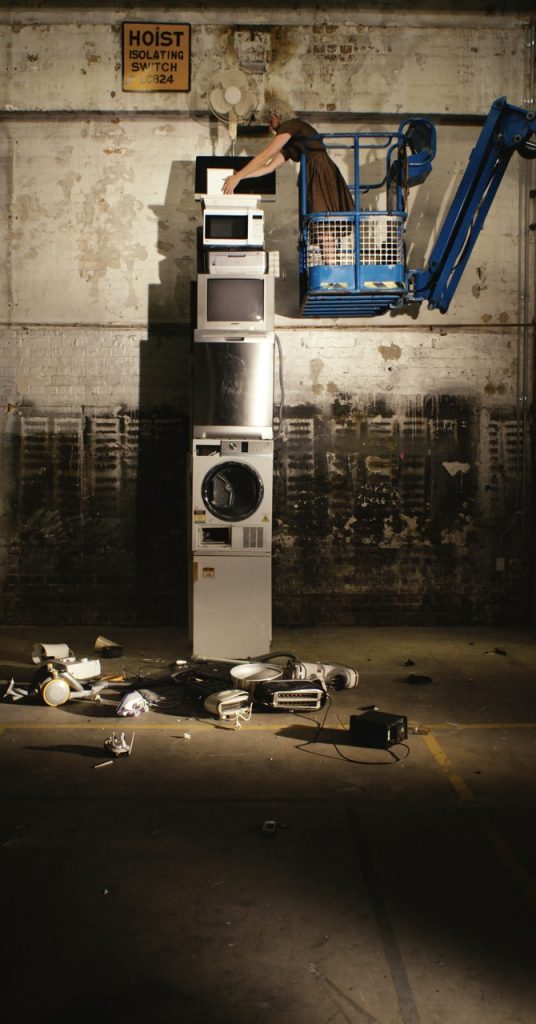

The art world tends to shy away from destruction. Often when destruction takes place in a gallery or museum —sites devoted to the preservation and protection of cultural material — something has gone awry. However, against this understanding, destruction is a powerful and tantalising idea that can generate new forms of knowledge, aesthetics and exchange. In the case of British artist Michael Landy, destruction has served as a key impulse in his practice. In his performance Break Down (2001), which brought the artist to international attention, Landy gathered his 7, 222 possessions in a former clothes shop in central London on Oxford Street, London.

Functioning as a forum of ownership and self, the project was witnessed by public who watched a team of assistants dissemble Landy’s possessions methodically, with each object eventually broken into its material parts, sent on a conveyor belt and sorted neatly into different material categories. Landy finished Break Down with nothing but the blue boiler suit which he had worn during the two-week projectand nearly six tonnes of debris which was taken to landfill.

There is a fascinating thread that connects Landy’s practice of carnage as a creative act, and how we understand the past through the archive (which can arguably be regarded as left overs of history):

- In Landy’s world nothing is forever, yet the archive is an attempt to preserve history forever;

- Landy’s Break Down was a comment on systems of value — what’s important and what matters in contemporary society; similarly, an archive seeks to preserve objects in the hopes that are judged as important with time;

- Many of Landy’s works exist as monuments to failure, and the archive is often a repository of failure, documenting stillborn projects, and half-ideas as in the case of Landy’s own Kaldor Public Art Project history.

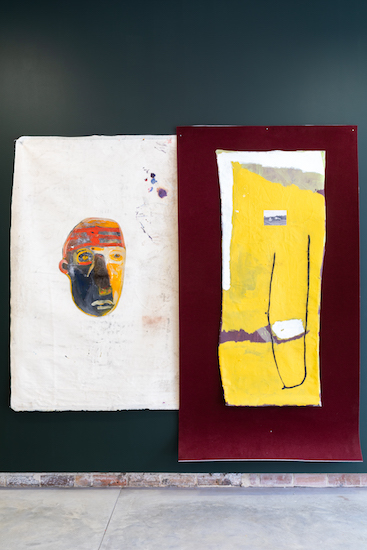

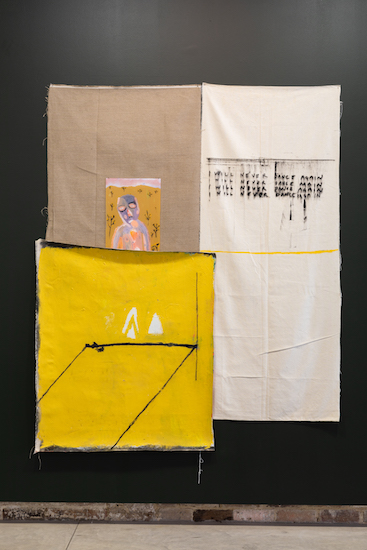

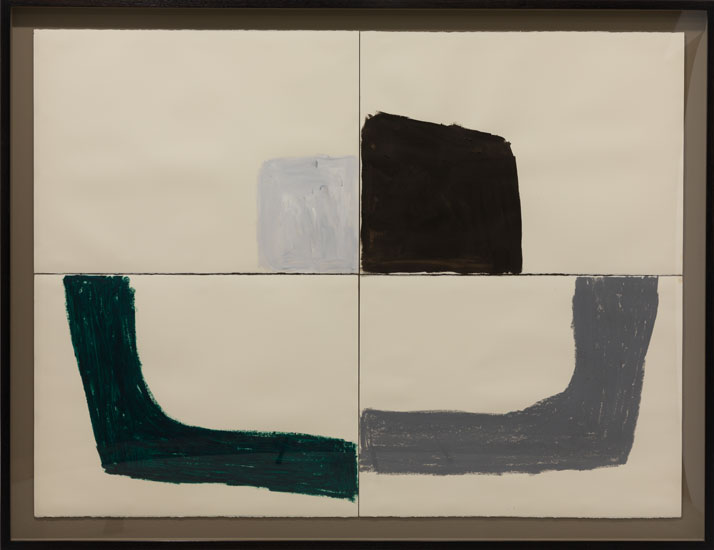

For Project 35: Making Art Public the artist conceived the exhibition as a series of 4m x 4m x 3m tall archival boxes, which contained archival materials, newly commissioned works, along with various exhibition strategies to reconstitute the projects, without necessarily restaging them. The idea was to break down and re-imagine the Kaldor Public Art Project Archive into its constituent parts, unveiling the guts of each project as a way to examine the organisation’s fifty year legacy.

Making Art Public: 50 Years of Kaldor Public Art Projects from Kaldor Public Art Projects on Vimeo.

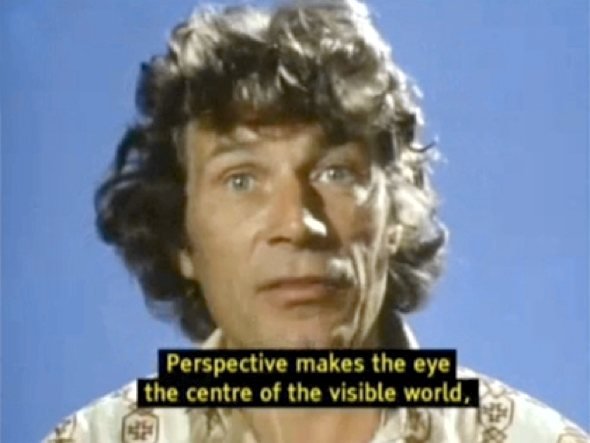

2. What can images achieve?

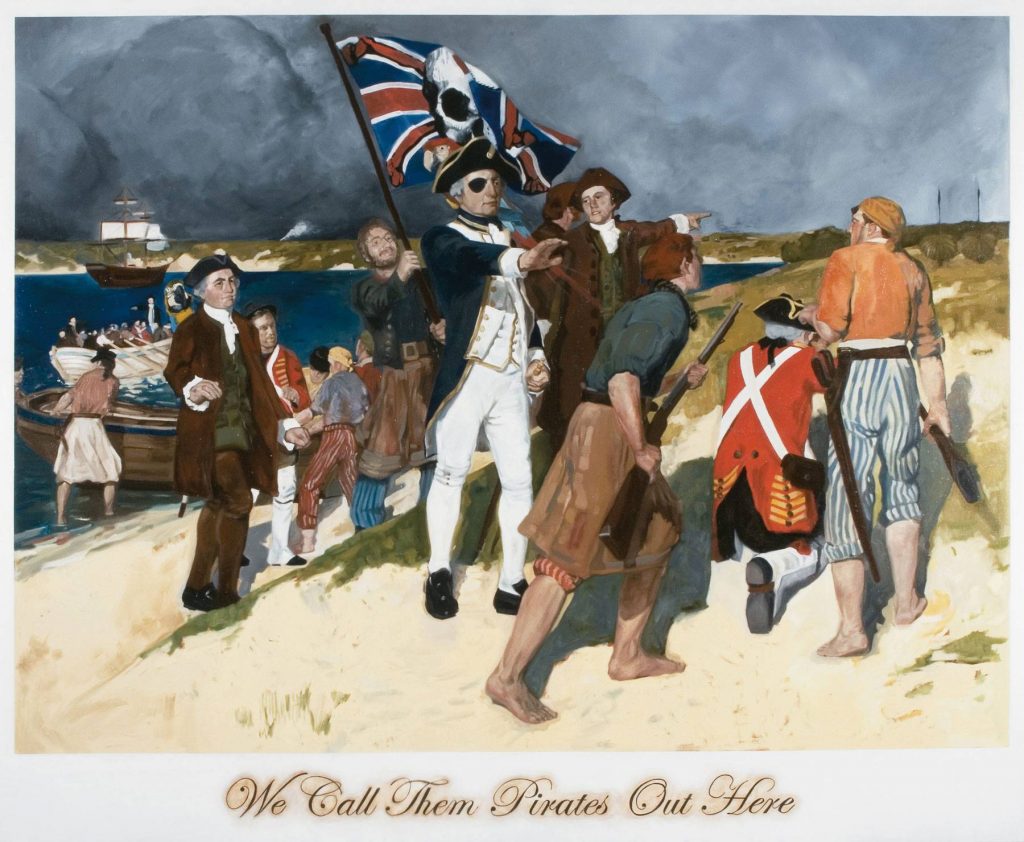

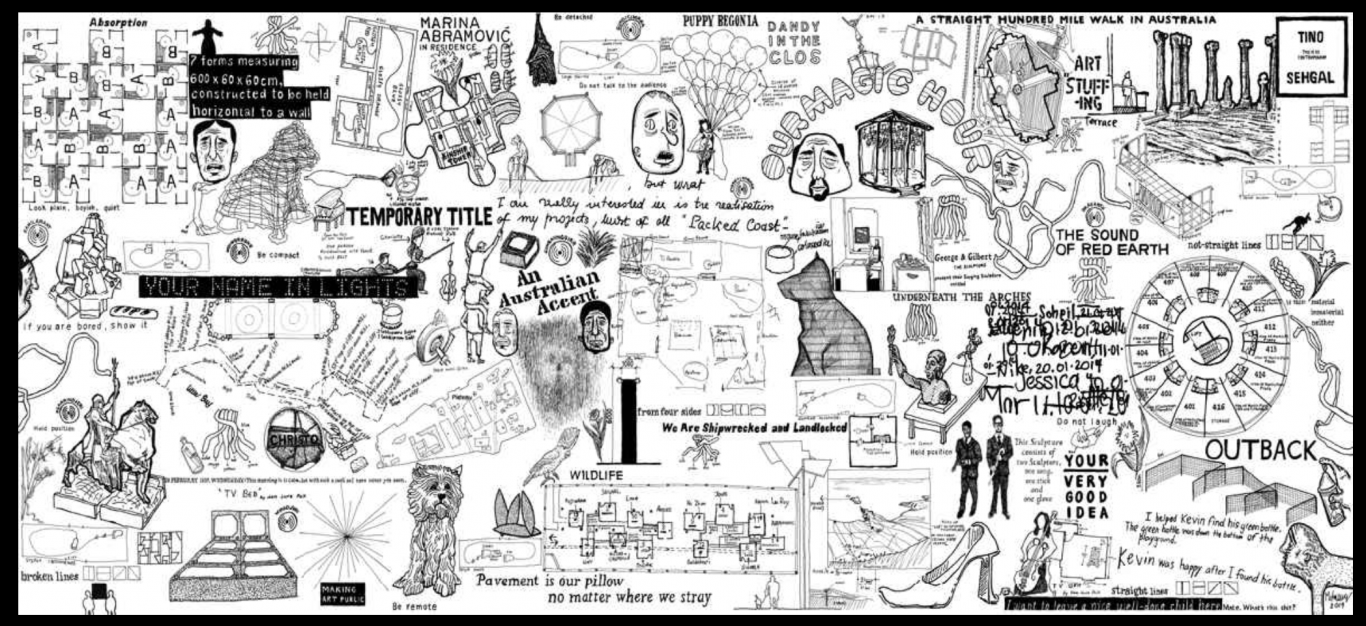

One of the first objects in the Project 35 archive is this item, a drawing by Landy. The title draws from an encounter between John Kaldor and a member of the public during Public Art Project 16: Gregor Schneider’s 21 Cells (2007) when the artist installed 4x4m steel cells on Bondi Beach in Sydney to resemble a prison. The work commented on terrorism and detention, issues occupying Australia’s political consciousness at the time. Reflecting an Australian irreverence in questioning of the purpose and meaning of the work, the man asked Kaldor, “Mate, what is this shit”? While Landy didn’t title the retrospective this, despite wanting to, he eventually found a use for the title — this work.

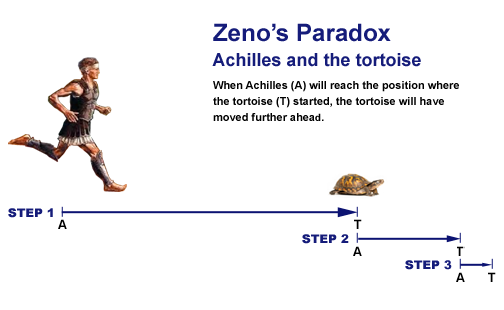

Mate. What’s this sh**t? captures the essence of the creative process. For artists and curators alike, the process of making an artwork, or putting together an exhibition is like tree climbing. As you struggle upwards, you’ll meet different branches which you must choose between. And similarly when you make your way down, you may take the same path, or more likely, opt for a different path altogether — all while without an aerial overview, or a map to plot your travel. And yet somehow, when recounting the making of an artwork (exhibition making, or tree climbing) after the fact, your decisions seem so self-evident, knotted together in a neat narrative. And while there exists a tendency to explain an artist’s process or an exhibition process as a streamlined, coherent narrative, these explanations have little to do with reality. Creativity is a rhizomatic process of searching, stopping, questioning, figuring, and asking. There is frustration, confusion and struggle.

And I felt this drawing really captured this sense: the organised chaos, the non-linearity and the interconnection.

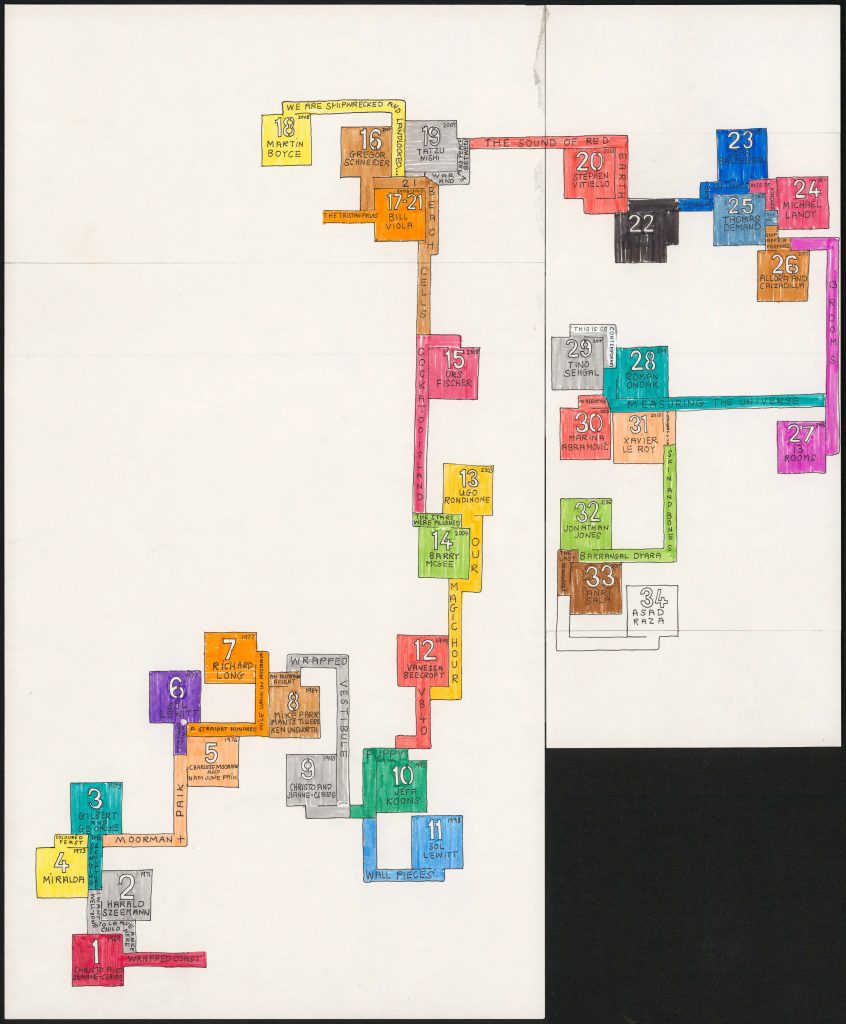

3. a set of aesthetics

I was particularly drawn to this floorplan as it conveys the importance of spatial awareness and audience experience in developing any exhibitions. For all curators, it is crucial to understand how audiences will interact with artworks. This is an interesting document that offers insights into how Landy — as both an outsider to Kaldor Public Art Projects (he’s not part of the ongoing team) and insider (as a former artist/collaborator) — made sense of the projects, and how audiences might engage with them. While the image displays a chronological floorplan, Landy eventually opted for a non chronological plotting of the exhibition, reflecting my actual experience of the exhibition at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, which was more haphazard and messier. These were qualities that I very much enjoyed as I discovered different archival boxes out of order and seemingly, without a clear, rationalised logic. Such a layout reflects more recent curatorial trends to create exhibitions that complicate (rather than dictate) the relationships between objects.

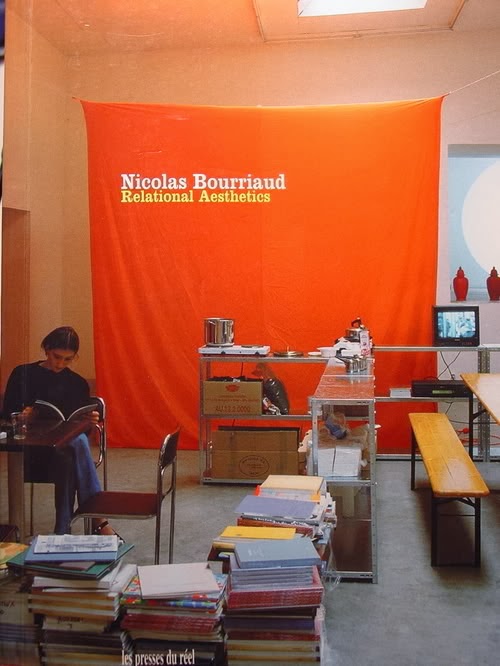

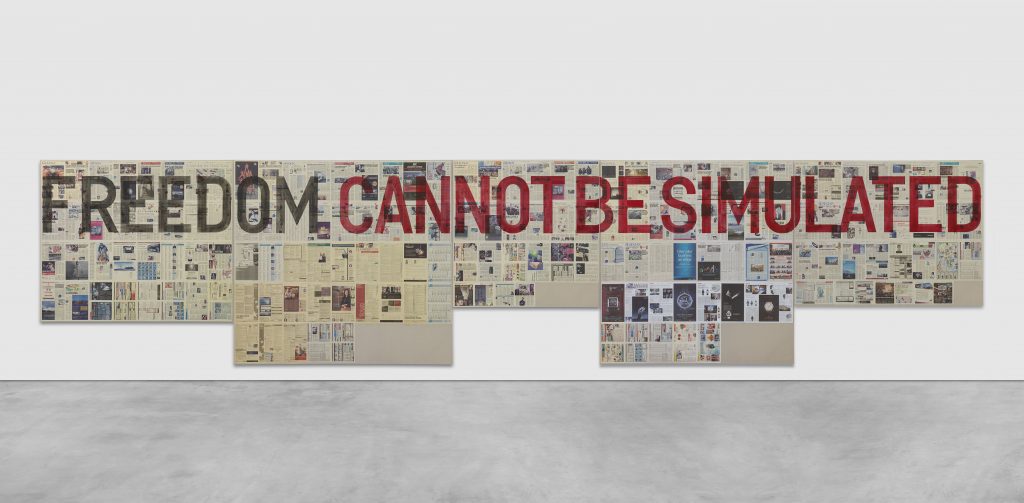

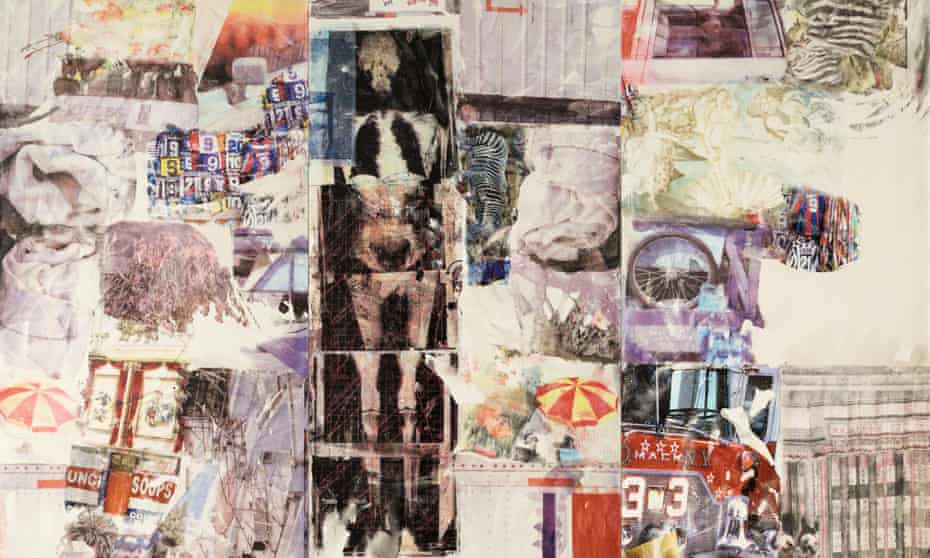

By way of context, the collision between the archive and exhibition gained traction in the early 2000s. American art critic and theorist Hal Foster titled this shift, the ‘documentary turn’ or ‘archival impulse’ and illustrated this shift with the example of influential Nigerian-born, New York-based curator Okwui Enwezor’s Documenta 11, Kassel — considered a landmark exhibition in the visual arts by many Western curators and scholars. The exhibition featured several artists who used documentation and the archive to explore how, and create new paths for images, texts, narratives, documents, audiences, and institutions to relate to one another. For an in depth discussion of the exhibition, consult Anthony Gardner & Charles Green.

4. systems of information

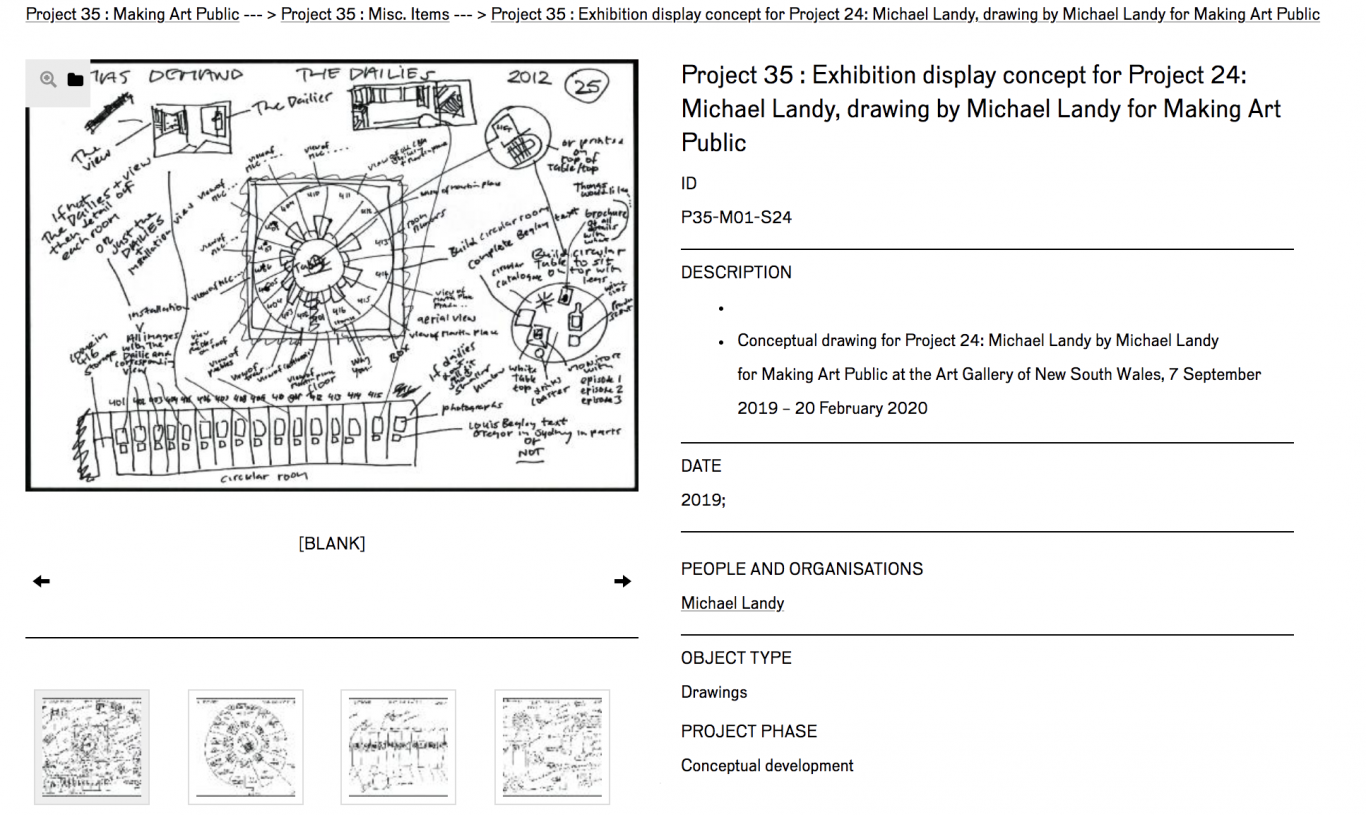

Much has been written about the archive and how it influences and interreact with society. The idea that the archive is inseparable to systems of power and knowledge was brought to prominence by French theorist Michel Foucault (The Order of Things, 1966, and Archaeology of Knowledge, 1969) and expanded upon by Jacques Derrida (Archive Fever, 1995). One of their key arguments was that the archive was inherently political, and archives can never be neutral or innocent as they are not encyclopaedic. Archives record history from a very particular context and perspective. As consumers of information, we must question the authority of the archive and recognise its limits as a complete record of history. As with all official records, absence and distortion exist.

In my research of Project 35, I wanted to understand how Landy would re-interpret his Project 24: Acts of Kindness, where he created a 13-metre installation in lower Martin Place that mapped the Sydney CBD to reveal where 200 stories of kindness were placed throughout the city streets. Unfortunately, there was an error in the archive. Project 24 contained material for Project 25, Thomas Demand’s The Dailies (2012) — an error which perfectly speaks to the critical idea above — archives are in fact another form of fallible human record subject to accidental and intentional distortion.

5. unexpected questions

This year is the fiftieth anniversary of American art historian Linda Nochlin’s Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? (1971) — a landmark essay that analysed how women have historically been barred from achieving success in the art world. She explains that institutional barriers (like organisational structures, terminology, and coded systems) rather than individual barriers (i.e. an inherent deficiency in female artists) could explain the lack of ‘great’ women artists in the Western art tradition.

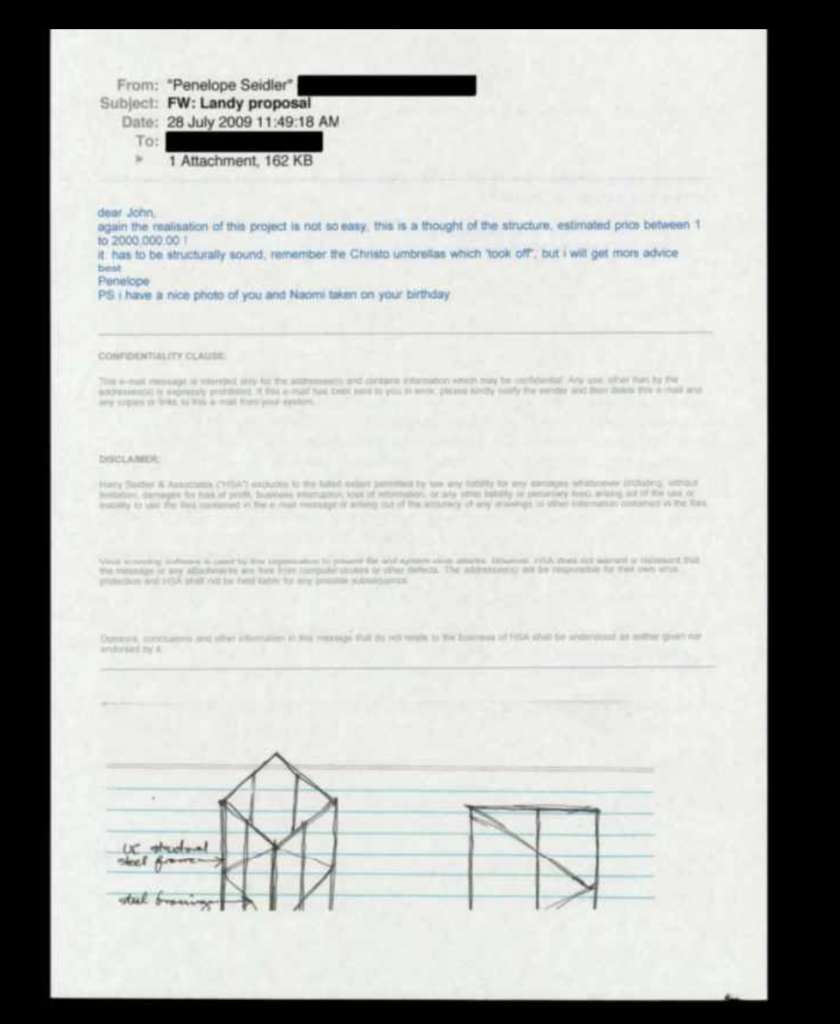

It was serendipitous that I discovered this email correspondence between John Kaldor and Australian architect and arts supporter Penelope Seidler. Until more recently, Seidler’s role in supporting the first Kaldor Public Art Project, Christo and Jean-Claude’s Wrapped Coast – One Million Square Feet, Little Bay, Sydney, Australia (1968–69) where the artists wrapped the coastline of Little Bay, Sydney in fabric, had largely existed as part of the oral, rather than written history of the project. As noted by gallery director Rebecca Coates, Seidler was left in charge of the Sydney project and corresponded between Kaldor and the artists while he was abroad during August and September 1969. It’s a lovely note to find in light of Nochlin’s essay and for me a real testament to Seidler, her vision, commitment and practicalities which are finally being recognised in the wider public sphere.

6. if there’s one thing you could destroy, what would it be?

Artmaking for many artists seems to be a form of faith, a private foray into the unknown. From my relationships with artists, the process of making art is like reaching a hand out and feeling around to find innovation, beauty, meaning and originality. But sometimes, much like any faith, prayers can go unanswered. Prior to Acts of Kindness, Landy had proposed several projects that remain uncompleted. I mention these projects as I believe that failure, for many artists, curators — and especially in Landy’s case who celebrates failure — is fundamental to realising creative outcomes. In an interview with Landy, he noted “all artists dream about people talking about their work, responding to it and remembering it. No one wants to make art that people forget”, and with these unrealised projects, Landy is true to his statement.

7 & 8. back and forth

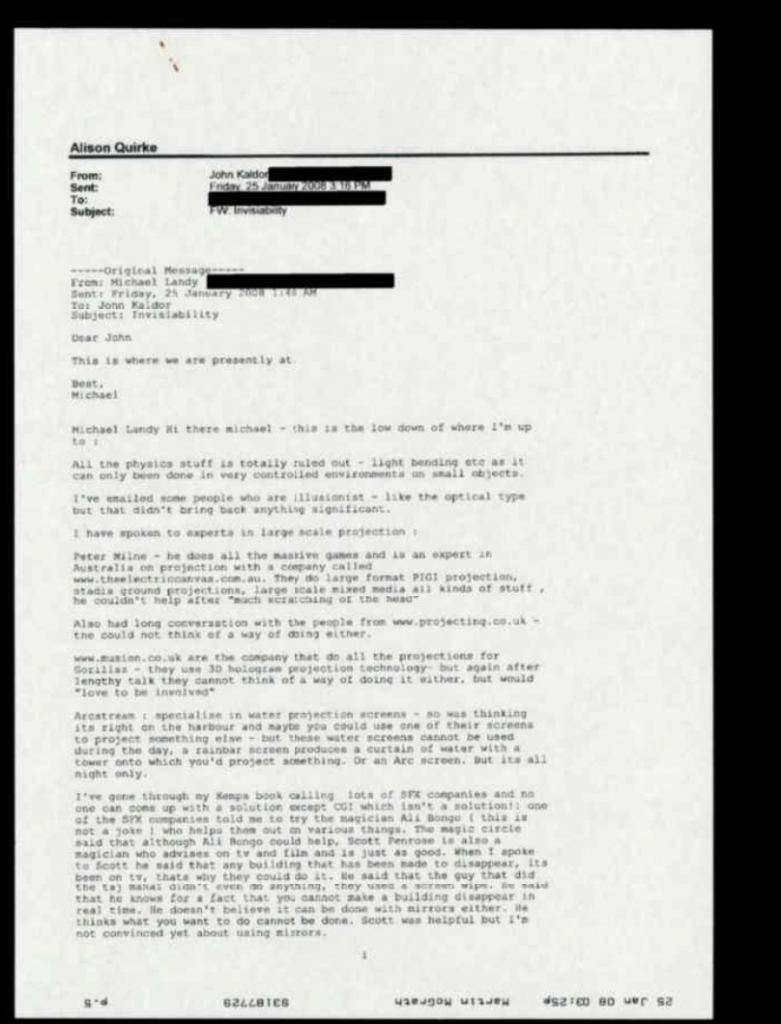

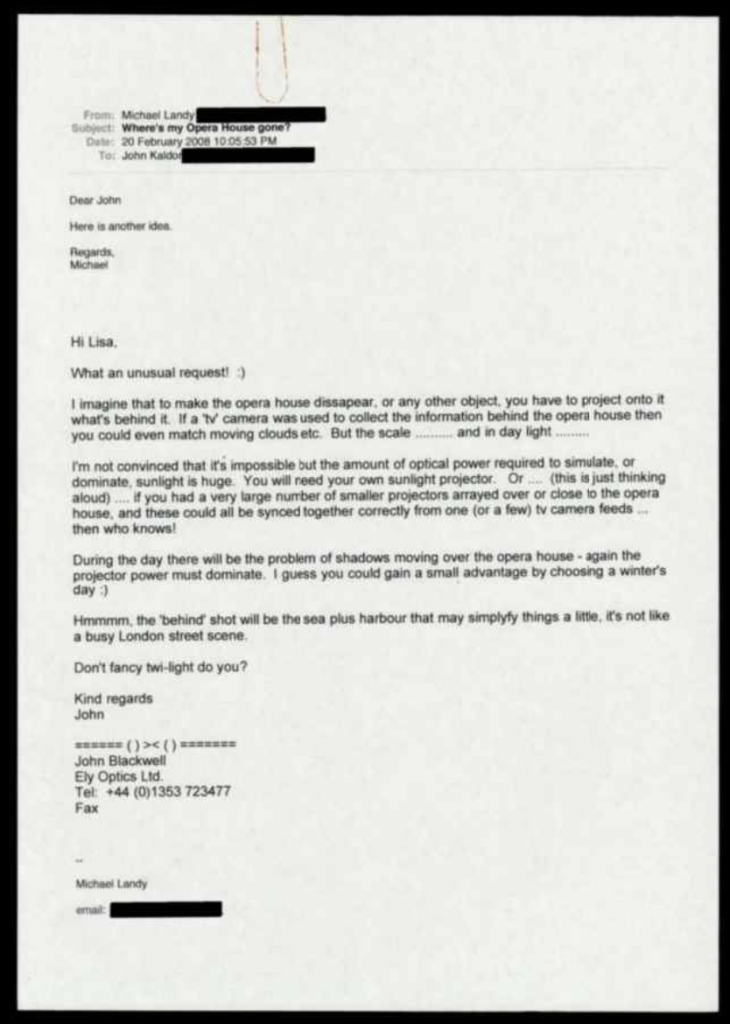

Right: Email from Michael Landy to John Kaldor containing suggestions for achieving an invisibility project in Sydney, specifically making the Sydney Opera House disappear, 20 February 2008.

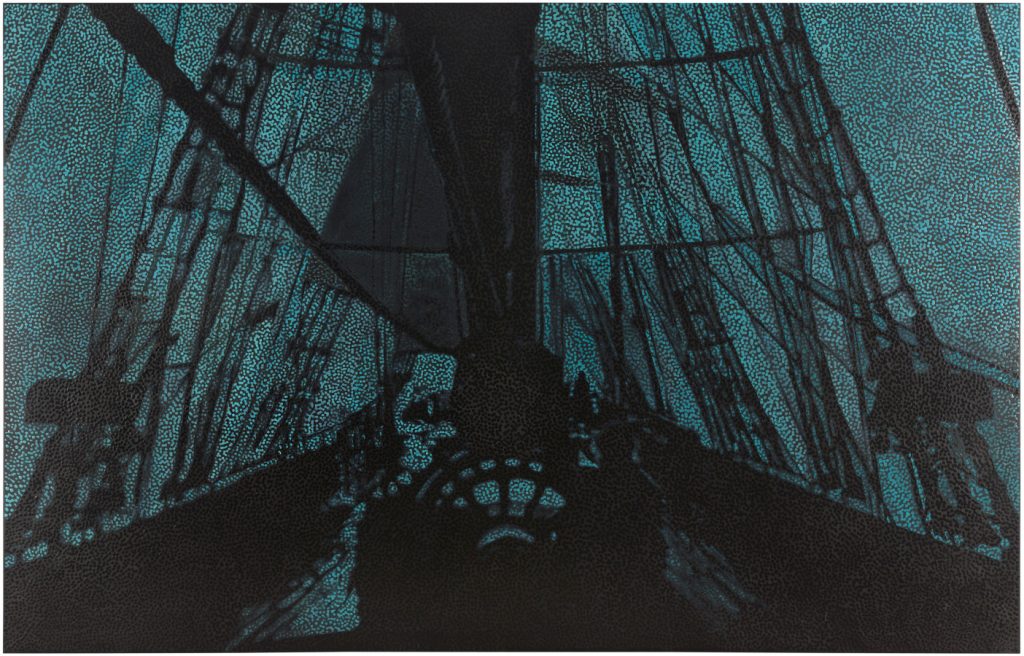

Landy proposed to disappear the Sydney Opera House’s clouds (which often are referred to as the building’s ‘sails’) — taking on one of the most iconic Australian buildings and intruding upon it. The correspondence illustrates the back-and-forth problem solving required to achieve a project like this, while underscoring how art is not a discrete field, but something that flows into and out of various other disciplines and industries.

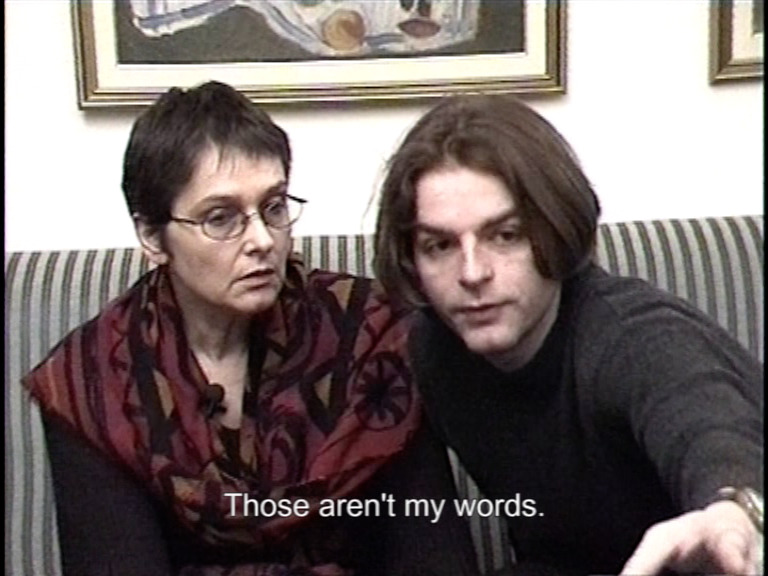

It’s also interesting to note that Landy himself does not keep an archive of his own practice. After Break Down (2001), the artist opted not to keep an archive. At the time, German artist Wolfgang Tillmans, who had just won the Turner Prize in 2000, documented Break Down (2001) in 106 photos. Months after the project, he sent the images to Landy in a box where they remained for twenty years. They were recently published in the newspaper The Financial Times. Landy admitted, had the photographs arrived during the project, they would similarly have to be destroyed with the rest of his belongings, available here.

9. the price of things

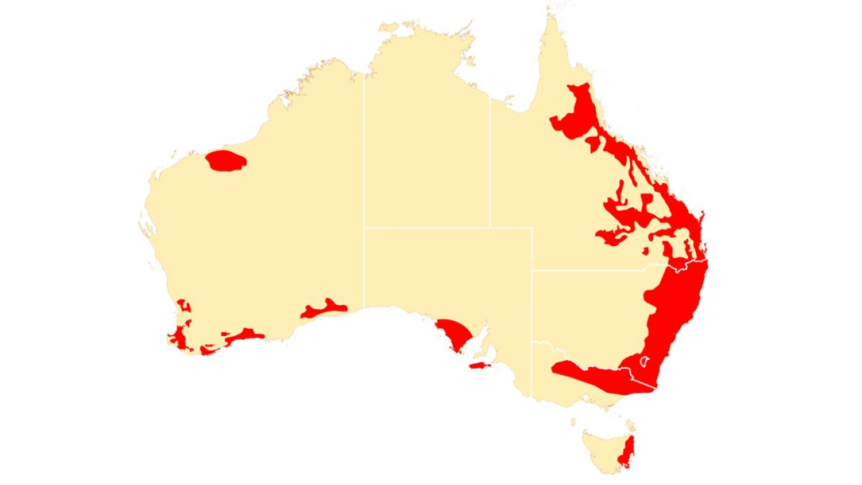

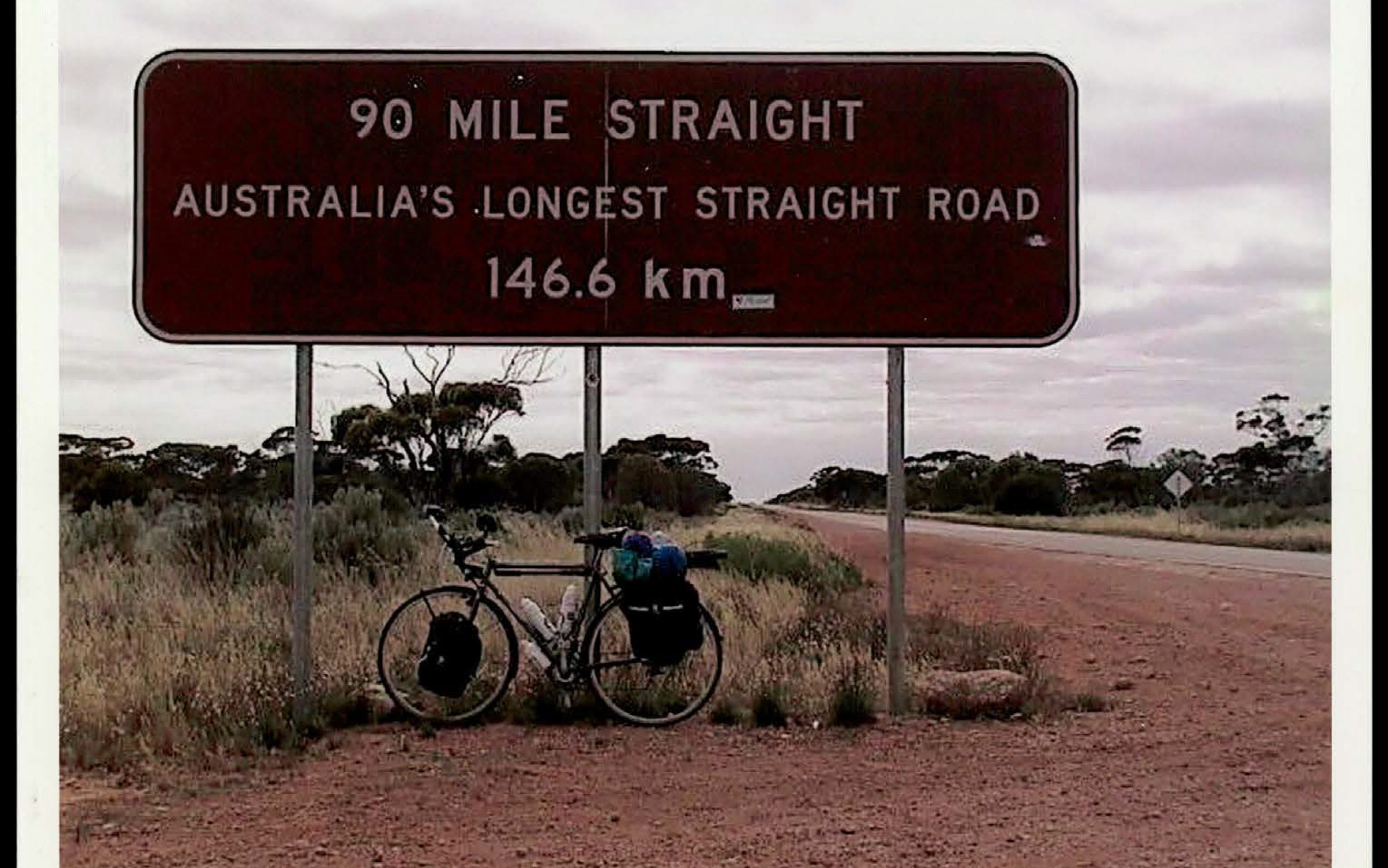

Another suggested project was Bend in the Road where the artist proposed to put a bend in Australia’s longest road, which measures 146.6km long in Western Australia. The estimated cost to relay one kilometre of road in remote Western Australia was $350 000 – $400 000 per kilometre (in 2009).

10. a cluster of possibilities

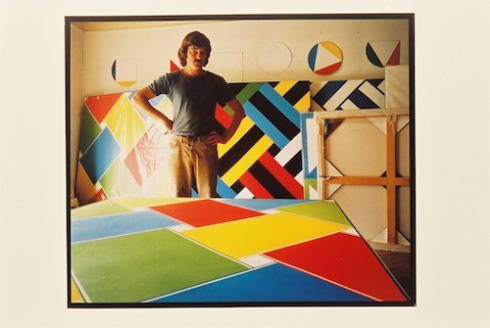

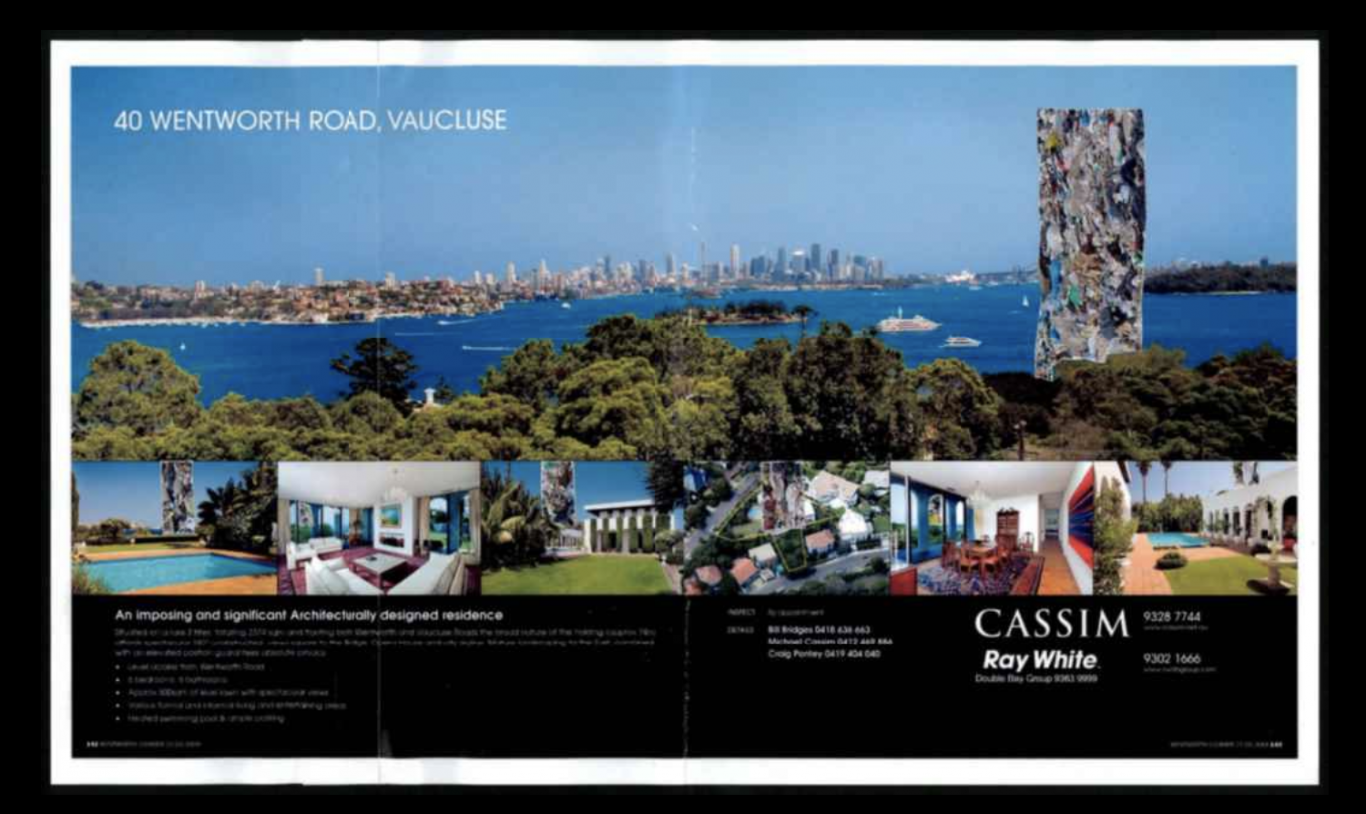

Landy also proposed House Stack, a sculptural tower comprising houses stacked vertically on top of one another. In a series of correspondence between John Kaldor and his team, the issue of expense comes up a few times. An early estimate provided by Seidler was in excess of $2 000,000. It is a clear illustration from these unrealised examples that creativity and the visual arts are very much connected to capital and money.

11. destruction (cont.)

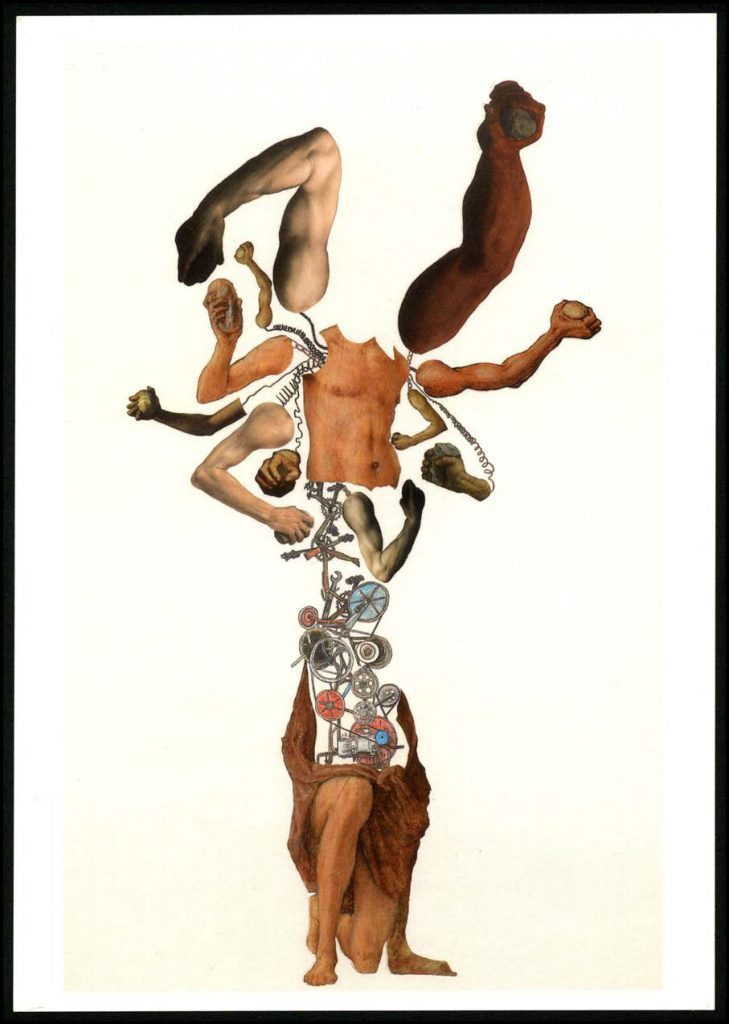

The best types of working relationships with artists are the those which extend far beyond a single exhibition into a lifetime of exchange. I thought that this postcard, sent to John Kaldor in the lead up to Landy’s exhibition, Saints Alive at the National Gallery, London illustrates their respect for each other. The exhibition grew from an invitation by the National Gallery of a two-year residency at the gallery. After this period of residency, Landy’s ideas culminated in an exhibition of kinetic figures of saints, who, with all the clumsiness of Victorian automata, attacked their own bodies with the instruments of their martyrdom.

The exhibition, which I saw, was captivating in the flesh. The works were Landy’s way of animating these two-dimensional works in the Gallery’s historic collections. In a very different vain but related to the eventual Project 35: Making Art Public project, Landy was pulling people into the paintings by animating them through these chimeric sculptures — much like the very different looking, but equally inviting archival rooms of projects that pulled audiences in, around and through the exhibition. Part Frankenstein’s monster, part Victorian steam machine, Saints, alive captured the saints in all their grandiosity, but foregrounded their destructive and martyred narratives.

Earnest, lyrical and beautiful. And following from Landy’s quote (point 5), hardly forgettable.

12. on and on

In leading you into the archive, I wish to also lead you out the other end. Over the past several months, I have worked with Kaldor Public Art Projects and three high schools to animate the Kaldor Archive through a series of student led ‘exhibitions’ that have taken the form of Instagram pages, PowerPoints and texts. Using this text as a springboard for the students, and corresponding with them through Zoom and detailed annotations given via Google, the process has been one of learning and insight.

Many of the students had existing understandings of the archive – whether their phone photo albums, text logs or diaries – and the through light guidance and the occasional prompt, they were able to apply their virtual search skills and curiosity to the project and develop rich exhibitions that both riff on the archive and are archival in themselves. There’s a lot to grapple with and even more to learn from their texts; take your time and experience the work of these Future Curators. And hopefully, you might catch Derrida’s Archive Fever.

In the meantime, I leave you with another artist whose process might also be described as archiving ‘junk’…

END.

_________

This text was commissioned by Kaldor Public Art Projects as part of the Future Curators Program, where three Australian curators researched the Kaldor Archives to develop a text/exhibition that could be used as an educational resource in NSW secondary schools.