gods who walk among us

October 2020

As English theorist and writer John Berger reminds us Ways of Seeing (1972), in the secular age, sacred art is considered more in terms of its provenance than its message. Yet despite this, sacred art — artworks with religious content or spiritual connotations — have significant currency in our contemporary world. Perhaps a rather corporate analysis, but sacred art examines how societies negotiate shared space and identity — and how these formulations are defined and defended. It is against our tumultuous coronavirus realities, and this desire to understand collective identity and ask, ‘who are we?’ that artist Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran has created his latest project Avatar Towers (2020) for the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

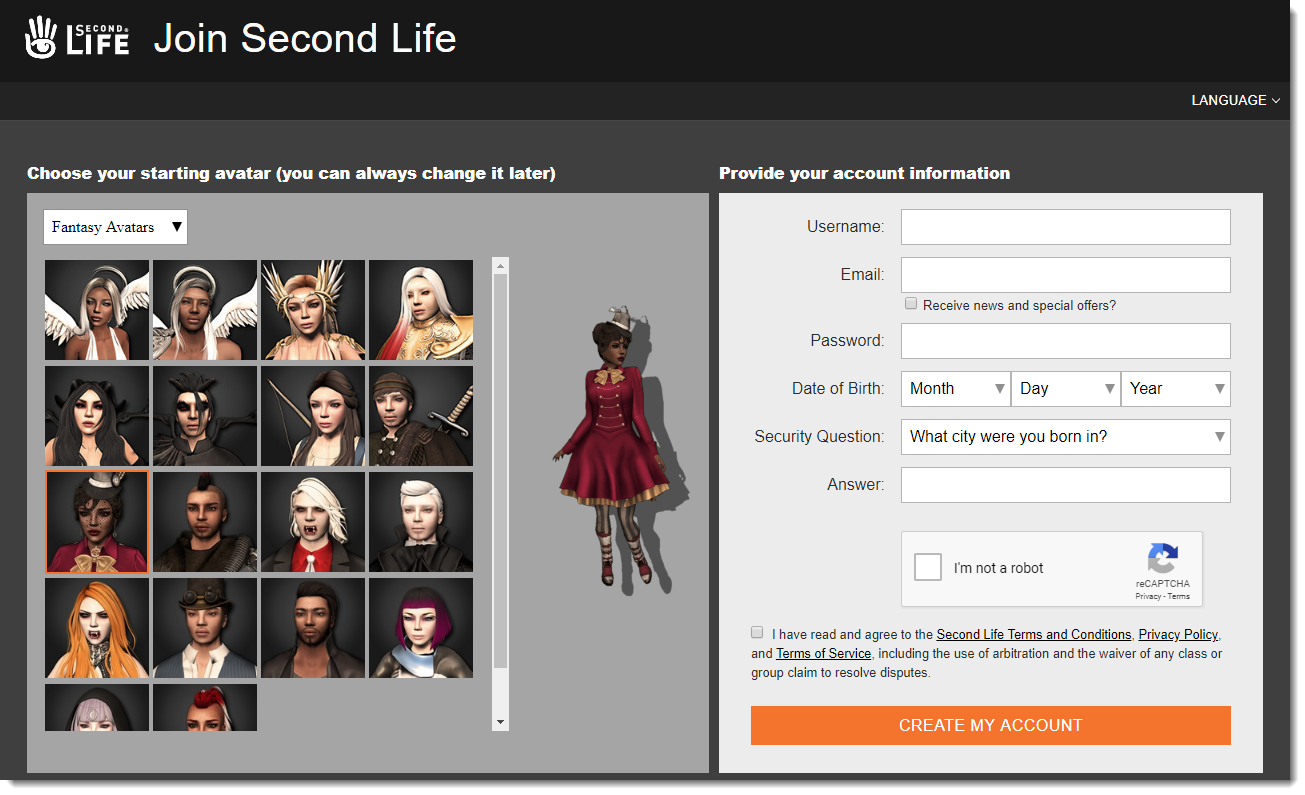

The concept ‘avatar’ from which the project’s title borrows is derived from Sanskrit, the sacred language of Hinduism. First appearing in the English world in the eighteenth century, an avatar is an incarnation of a deity, and is closely associated with Vishnu, a principle deity. Hindu belief holds that his ten incarnations — which include a fish and a half-man and half-man-lion — would restore order on Earth when humanity descends into chaos. From these celestial beginnings, the concept has since been absorbed into the language of the online, including multiplayer computer games like Second Life and platforms like Twitter, Tumblr and Slack. Founder of Second Life, Philip Rosedale defined an avatar as “the representation of your chosen embodied appearance to other people in a virtual world.” In this way, virtual avatars exist, appear and behave at the complete discretion of their users — enabling online users to embody the role of god.

Located in the gallery’s entrance vestibule — its main entrance — Avatar Towers comprises of a monumental tableau of seventy bronze and clay figures organized within and around a five-meter roughly hewn together structure topped with a ceramic stupa — a mound like structure that holds relics used for meditation. Taking over this threshold space, these avatars, rendered in Nithiyendran’s recognizable punk-queer-maximalist aesthetic, are ceremonious in their monochromatic and polychromatic mystery. They appear turbocharged with glaze, contorted into impossible proportions, pummeled by the artist hands and fired by the kiln — characteristics which hint at the cacophony of internal stories held within each figure. Veering back and forth between fantasy and reality, these characters function as a sort of portal: a hall of mirrors that distorts and transforms meaning, sparking of rushes to the imagination as we explore Nithiyendran’s universe.

Within the installation, Nithiyendran has selected two stone sculptures drawn from the gallery’s collection: a stone Javanese Ganesha — a deity which personifies wisdom and intellect — and a stone Gandharan Buddha — which represents the ideal state of ethical and intellectual perfection attained through kindness. The inclusion of these sacred objects provides a powerful locus for the project — highlighting the parallels and differences in sculptural languages used to portray deities throughout Asia, while connecting Nithiyendran’s contribution to the field of figurative religious sculpture. Today, where religion has seemingly been overtaken by less lofty dogmas — including the cult of the celebrity, wanton consumerism and a desire to shock — their inclusion in this installationreminds us that contemporary art, despite however untraditional can hold the old fashioned aura of spirituality, a quality largely relegated to the fringes of art criticism and production today.

The work will be placed in the vestibule of the Art Gallery of New South Wales. The placement of the work in this location (where all visitors must pass) reflects a growing desire for public institutions to open their traditionally conservative doors to new cartographies of practice outside of dominant Western narratives. By manifesting and exhibiting an installation which can be read as a quasi-religious non Judeo-Christian shrine, Avatar Towers re-territorialises the cultural and physical space of this sandstone institution — and arguably its most important space, its entrance — from the dominant white narratives that have marginalised and misrepresented categories of difference.

This spirit of cultural intersection and hybridity has long formed the bedrock of Nithiyendran’s engagement with ceramics. He notes, it is a “medium burdened with a history of politeness and good manners … as a contemporary artist, I want more. I want to be challenged and encouraged to engage with the world in critical and uneasy ways. I want art that reflects the social, technological and philosophical developments and concerns of our time and place.”[1] In continuing this spirit, Nithiyendran has experimented with industrial automotive spraying processes to create rich monochromatic finishes. He explains, “I was thinking about painting as a language, philosophy and a gesture and thinking about glaze in relation to that. The auto spray mimics glaze in this way and I wanted to experiment with this technology. It’s not possible to get these sorts of finishes from traditional kiln processes and I’m unwilling to confine myself to these glazes.”[2]

Of the sprayed avatars is a monochromatic hot pink fertility figure. Fertility figures — which exist all throughout antiquity across different cultures — have historically been represented as women. However, Nithiyendran has decided to render this figure, among several, as gender neutral or multigendered. This dissolution of longstanding binary understandings of gender speaks to Nithiyendran’s desire to reimagine structures, histories and aesthetics to create space for multiple voices, readings and realities.

Ultimately, Nithiyendran chorus of characters exist to lure and entrance audiences into his technicolored ceramic world pregnant with counter-narratives for our current pandemic related uncertainty. Through the metaphor of the avatar, Nithiyendran manages to both recognize the aesthetic, political and spiritual dimensions of art and spirituality, without reducing the project to either. In this way, Avatar Towers engages in a discussion of collective identity, raising questions of what divides and unites us. How do we negotiate separation and intimacy? And ultimately, who are we and what is our collective place in the world?

How we choose to answer these questions will ultimately shape new forms of togetherness — and isolation.

END.

This text was originally published in S+S Magazine.

References:

[1] Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran [online]. Journal of Australian Ceramics, The, Vol. 57, No. 1, Apr 2018: 44-[45]. Availability: <https://search.informit.com.au/documentSummary;dn=529057343940793;res=IELHSS> ISSN: 1449-275X.

[2] Interview with artist