The Economics of Solidarity

May 2020

Over the past half century, the visual art world has undergone an exceptional transformation, with the public, private and commercial art spheres booming with greater ambition. Underwritten by the availability of capital and connectivity, visual art has never been so available to collectors, accessible to appreciators and outward looking in its approach, enveloping a range of cultural references, societal movements and technologies. These circumstances have birthed generations of artists who now work in contexts far removed from the solitary, tortured artist-as-martyr-madman-shaman conceptions that once prevailed. In order to earn their living, artists today rely on a complex ecosystem of support structures that include public and private grants, prizes, galleries, commercial opportunities and private philanthropy.

Their careers tend to be guided by amorphous and transient opportunities that are contingent on timing and circumstance. In navigating this reality, artists must rely on their entrepreneurial skills to move and work across different projects, events and galleries. These working conditions are further compounded by a financial insecurity, the lack of discernible career structures, trade unions and the social benefits that other industries take for granted such as a fringe benefits. This precarity has made the sudden fall brought on by coronavirus much more painful for artists. Every aspect of the art world, from the mightiest museums, to emerging artists have been devastated by the pandemic lockdown, with the economic futures of the sector left uncertain.

While an economics of solidarity is finally emerging, with private foundations and state and federal government supporting Australian artists, these opportunities are nonetheless coloured by the limited view of how Western societies understand visual art and capital. There is a dissonance between the cultural value and the capital value of artists. This is in part explained by the difficulty in quantifying artistic labour which is often intangible and exists independent from formal markets where prices can be easily determined (say a slice of banana bread from your local café or perhaps a gold bullion bar).

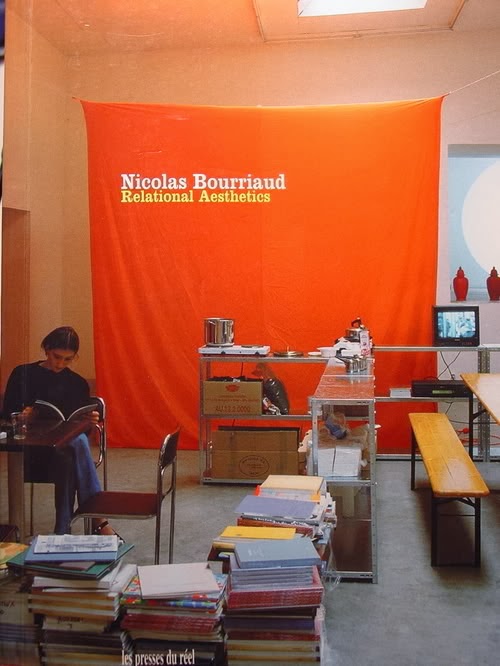

In grappling with this tension, artists have developed strategies to challenge the ever-accelerating cycles of consumption and obsolesce in the Western world; conceiving of art world disconnected from the capitalist systems of exchange that force artists to work and exist so precariously. For example, French curator Nicolas Bourriaud observed a generation of artists in the 1990s who drew upon strategies of institutional critique from the 1960s and 1970s whereby artists disappeared the art object in favour for art works and ideas that resist commodification. This movement, which he titled Relational Aesthetics, reframed audiences as a collective social entity capable of temporary utopian encounters.

Artists like Liam Gillick, Rirkrit Tiravanija, Christine Hill and Vanessa Beecroft created contexts where audiences could resist the intensely commodified, transactional and virtual relationships heralded by Globalisation. These gatherings, which Bourriaud called “microtopias’, were opportunities for audiences to pause and inhabit the world in a different way. The artist was the designer of social interactions, co-opting their audience through different prompts to create art gatherings disconnected from the typical acts of purchasing, contracting and schmoozing that typically take place.

This historical movement is an example of artist led cultural reform that emphasises human care and empathy above economic interests. While critics like English historian Claire Bishop have criticised Relational Aesthetics as a toothless naïve exercise, the movement’s idealism is critical in reconciling the role of artists, and to understanding how and why our era of hyper Capitalism has let them down. These relational encounters offer us a loose template for care and consideration that will guide us through this crisis. After all, without imaginary ideals like this, there is no possibility of a radical reimagination of this status quo.

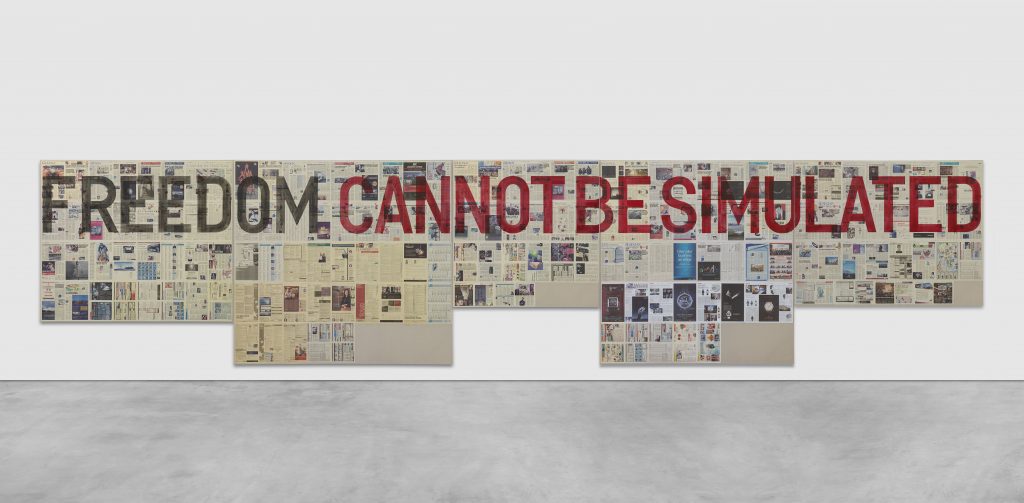

The coronavirus pandemic has foregrounded the wealth inequalities in all industries. In the case of the cultural sector, vulnerable arts organisations, arts workers, and artists are clamouring for answers. And in this uncertainty, the pandemic offers the potential for action and leadership. This time calls for a recommitment to artists, resetting our all-pervasive economic rationalism in favour for a system of open-ended concern for human wellbeing and quality of life — expanding Bourriaud’s concept of a ‘microtopia’ into a ‘macrotopia’. Such a system could include reduced working hours to ensure artists are better able to devote time to their practice in lieu of their day jobs, basic income guarantees, or a reorientation of existing state provisions that better compensate artistic practice — an extension of the economics of solidarity that has been partially put in place by the Australian State and Federal governments to tide furloughed or laid-off workers during the lockdown. Such measures would recognise the social value of creative endeavours, better protecting and supporting artists who are the creative backbone of the country. Artists do not act in isolation; much like anyone else, they affect and are affected by government and business decisions.

A new paradigm that redresses this precarity would also require the distinctions between the sanctity of art and the grubbiness of money to be collapsed. We must abandon prejudices against artists open to commercialism who are often vilified as sell outs. This system would also need to rewrite the idea that artists can be paid in ‘exposure’ and ‘opportunity’ instead of money for their time and labour. With this in mind, I have suggested propositions for contemplation and action while we rally together during the pandemic and consider how we can reset economic, social and historical relationships to build a society that we want. Only in this way, can we finally begin to recognise and the resolve the precarity of artists which has been for too long been ignored and dismissed as simply a necessary condition of art making.

END.

This text was originally commissioned and published by Art Collector.