in any given moment: eugenia Raskopoulos

August 2020

Representations of women in visual art have historically defined female experience through difference, weakness, passivity, sexual availability, domesticity and, perhaps most unintelligent, an object to be represented in art rather than a maker of art. For centuries these assumptions have dangerously masqueraded as normal; however, successive generations of artists have worked to rebut this putrid sexism that lies beneath the filthy bandages of Western art history. Eugenia Raskopoulos is part of this chorus of artists, producing work that untangles the relationship between women, art, identity and the veiled patriarchal power relations in Western society.

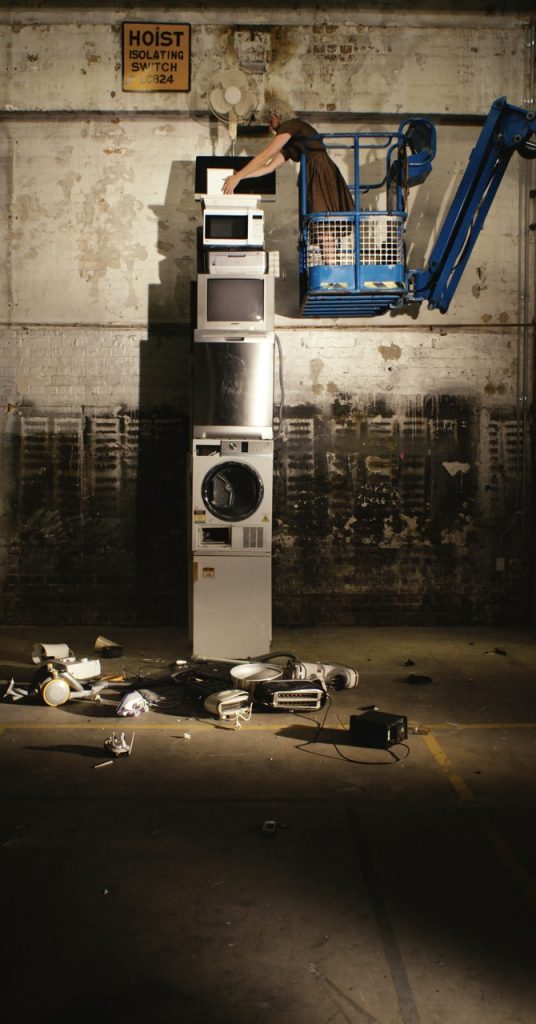

In her most recent large-scale installation, ORDER-(DIS)ORDER (2019) for ‘The National’ at Carriageworks, Sydney, Raskopoulos staged a performance where she topples a tower of discarded white goods, which was then projected onto the same site to achieve a ghostly palimpsestic effect that stretches conceptions of time and place. Alongside a topography of the destroyed white goods, the video-installation was framed by a neon pendulum sign alternating the words ‘order’ and ‘disorder’. Challenging the sexual power system of the patriarchy, Raskopoulos selected the whitegoods for their connotations of the domestic, feminine and servile, repurposing these objects and their meaning in a shattering act of apocalyptic and dystopic proportions.

In this process of creation and destruction, Raskopoulos confronts Western society’s conception of women as masters of the domestic universe. Conceiving of herself as a master-hero figure of a different sort, the work uses metaphor and symbolism to remind her audience that supposedly innocent objects, words and their associations have come to embody the status quo of structural sexism and a class system. And while these systems continue to restrict many women, small act of resistance like this are possible and available. In this way, Raskopoulos asserts text, images and objects are never simple, neutral tools that describe the world. They are coded by conventions and rules that reflect broader power relations. To understand any differently, is to be complicit in this system.

Throughout Raskopoulos’ forty-year career, the artist has maintained a deep interest in changing the present by challenging the ways in which we describe the past. She has woven her own image and experiences into a series of photographs, films and installations to articulate the constant negotiation that migrant bodies face in foreign cultures. She notes, ‘I am interrogating the concept of the fragmented body. As an immigrant – a Czech-born woman of Greek descent – my identity is made up of different parts that don’t always sit neatly together. And in the same breath, I want to defy all these labels and break apart traditional conceptions of the body, identity and art.’

Rootreoot (2016) embodies in this interest. The split frame video filmed in an aerial shot features two female figures played by the artist. In the upper section, the figure drags an olive tree in an ongoing clockwise circle, while in the bottom section the same figure simultaneously drags a wattle tree in the opposite direction. Moving at their own rhythms and in opposing parts of the video frame, the circles created by each figure eventually intertwine, creating a moment of completeness as the bodies meld into one another and then dissolve away, concluding the work.

The circular journey of the characters mirrors the complexities of migrant and female bodies, capturing something important about their daily experience. While not a strict self-portrait, Raskopoulos plays the central figure in the composition as she does in many of her other works. By drawing upon the tradition of the self-portrait, Rootreoot explores the interface between the way we present ourselves to others and how others see us. This technique forms part of the many artistic strategies employed by Raskopoulos to explore and challenge codes of thought and behaviour.

Complementing Rootreoot is Routereroute (2016), two circular neon signs that spell the title of the work – one in Greek, the artist’s first language, and one in English. Reflecting the duality of video work, these neon works depict the tectonic reality of migrants in which meaning, identity and conceptions of self are slippery and language (particularly the foreign language of a migrant’s new home) serves both to elucidate and limit these understandings. This particular experience – one of many experiences faced by migrants – speaks to Raskopoulos’ own experiencing growing up in Australia, when she was often required to translate English to Greek for her grandparents; ‘I was a translator from a very young age. That’s when I learned its power. If ever anyone would say anything mean to my grandparents, I would mistranslate the words and protect them … the discrimination we would face.’

Reflecting on her methodology, Raskopoulos notes, ‘I’m at my best when I’m in the studio. I’m happiest in the making process where you get to read and research. It’s all part of it, looking and relooking. I love the repetitive kinds of traces and motions that the body is working through. It’s an important life lesson – just doing this type of work and being diligent about it.’

In thinking about the next set of milestones, Raskopoulos gives little away about her upcoming project at Arc One Gallery, Melbourne. Scheduled for 2021, the works continue the artist’s lifelong flirtation with the power of language and photography as poetic metaphors for life. After all, as Raskopoulos conveys in her work, art is not simply a dream or a vision of a female nude; it’s the skeleton architecture of our lives. It lays the foundation for a future of change and a bridge across our fears to new ideas, to experiences and (if we’re lucky enough) to where we have never been before.

END.

This article was originally commissioned and published by Artist Profile.